Whether you’re looking for a mild sourdough to pair with butter or a tangy, full-flavoured bread that will stand up to a rich soup or strong cheese, these are the tweaks that can help you achieve your ideal sourdough.

We recently had the good fortune to attend a class at King Arthur Flour on the science of sourdough. The class, taught by microbiologist Debra Wink, focused on all the different tools the baker has to control the natural sourdough fermentation process. While Debra waxed poetic about six-carbon chains and weak hydrogen bonds, KAF pro baker Amber put us through our paces with two of King Arthur’s iconic sourdoughs: the mild and delicate Pain au Levain and the tangy Vermont Sourdough.

What we brought away from the class was a deeper understanding of the science behind some of our favourite sourdough tweaks. Below, we survey three key factors for influencing acidity in sourdoughs: temperature, flour choice and maturity. There are other factors as well, but these are the ones we find to be both easy to implement and highly effective.

Key Factors Influencing Acidity in Sourdough

| Less Sour | More Sour | |

| Mother culture | white flour. mature when fully risen. ferment at 21-24 ºC (when not stored in the refrigerator). | some rye and/or whole wheat flour. mature after fully risen. ferment at 28-29 ºC (when not stored the refrigerator). |

| Pre-ferment | white flour. ripe at or before peak rise. ferment at 21-24 ºC. | some rye and/or whole wheat flour. ripe after peak rise. ferment at 28-29 °C. |

| Main dough | less whole grain / rye flour. rise to 1½ – 2 times volume. ferment at 21-24 ºC. | more whole grain and/or rye flour. rise to 2¼ – 3 times volume. ferment at 28-29°C. |

| Final shaped proof | ferment at 21-24 °C. | ferment at 28-29 ºC. retard at 4-10 ºC. |

Sources: Debra Wink, Michael Gänzle, Brød & Taylor

Temperature. Temperature is the one variable that bakers can control at every stage of the bread making process, from Mother culture through the final shaped proof. It’s an easy variable to manage using water temperature and a Proofer.

- For less acidity, use water at around 27 ºC and a Proofer setting of 21-24 ºC to favour the yeast and create milder flavours. When the Mother culture is being kept at room temperature (for instance, for a few feeds leading up to bread making), consider giving it one or two short feed cycles, rising at 24 ºC just until peaked.

- For more acidity, use 32 ºC water and consider fermenting the Mother culture (when not in the refrigerator) and pre-ferment at about 28-29 ºC, which is warm enough to begin to give desirable acid-producing bacteria (LAB) an edge. Yet it won’t be hot enough to damage yeast populations, which are necessary for the ongoing health of the Mother culture and for good structure and rise in the bread.

Whole Grain and Rye Flours. Whole grain and rye flours provide minerals and enzymes that can influence acid production in sourdoughs. The higher mineral content of whole grains acts as a buffer in the dough so that more acid can be produced during extended fermentation. And the complex carbohydrate and enzyme content of rye flour helps produce unique sugars that tip the balance of acids in favour of acetic acid, which has more aroma and flavour and is more noticeable in the dough than lactic acid.

- For milder sourdough, use less whole wheat and less rye, or consider sifting the bran out of whole wheat flour to create high-extraction flour. If using small amounts of whole grain, save it for the main dough, where it will have less time to contribute to acidity.

- For more tang, incorporate some rye flour and/or whole wheat flour early in the bread-making process, such as regular Mother culture feeds and the pre-ferment. Rye flour in particular will help your culture produce some acetic acid.

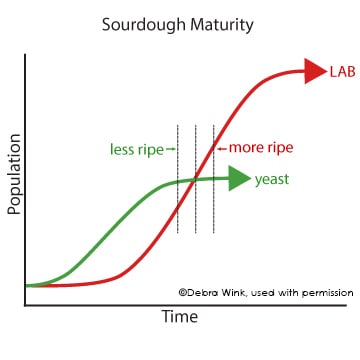

Maturity. In our experience, tweaking maturity is a highly effective way to control sourdough flavour. This applies to refreshing the Mother culture, fermenting the pre-ferment and rising the main dough (bulk fermentation). It does not apply to the final proof, because the point at which the shaped loaf is ready to bake should only be determined by the balance between gas production and structure. As Ms. Wink taught in her class, the reason maturity is so effective is that the acid producers (LAB) have a faster growth rate than yeast, so harvesting the culture when it is more ripe quickly shifts the population balance towards greater numbers of LAB.

- To limit acidity, refresh the Mother culture when it has just risen to its final height. Similarly, harvest the pre-ferment when it has just peaked or even before the peak, and limit the main dough (bulk) fermentation to a doubling of volume.

- To push for more acidity, allow the Mother culture to rest at its peak rise height for a while before refreshing. During the rest, the yeast population will hold steady while the acid producers (LAB) grow. Allow the pre-ferment to do the same – rest for a period after reaching its peak rise, then use it to mix the main dough. For the main dough (bulk fermentation), rise the dough to more than double its volume. Many sourdoughs can rise to 2½ times their starting volume and some will do great with a threefold rise.

In part two of this series, we use these factors to play with our tried-and-true Country Sourdough Recipe.

Deutsch

Deutsch Select Country

Select Country